1. The arrival of western culture: Greeks and Romans

The Greeks arrived in the territory that today is Catalonia in the 6th century BC. They founded two cities, Rhode (Roses) and Emporion (Empúries), and spread the basis of western culture: that is, their values and their social and political ideas for organizing society. Afterwards, from the 5th to the 3rd century BC, it was the Romans who took over and organized the territory, created infrastructures and established cities such as Tarraco (Tarragone) and Barcino (Barcelona). The importance of the Roman legacy is obvious in many ways. For instance, the Catalan language has its origins in the Latin spoken by Romans, just as Italian, Spanish, French and Portuguese also do.

2. The founding of Catalonia

Considered the founder of Catalonia, nobleman Count Guifré el Pilós (Wilfred the Hairy) is a historic figure. He managed to establish a territory between the Pyrenees and the sea, with its capital in Barcelona, at the end of the 9th century. This was the basis of what would be the future sovereign state of Catalonia. In the late 10th century, the Catalan counties stopped transferring taxes to the Frankish kings and, thus, became fully independent.

3. Parliamentary tradition

During the 11th century, a primitive form of parliamentary set-up already existed in Catalonia: the Assamblea de Pau i Treva (Peace and Truce Assembly). Formed by peasants and clerics, it aimed to limit the powers of feudal lords. Some years later, in 1283, one of the oldest parliaments in the world was created, Les Corts Catalanes, a deal-making system which prohibited the King from promulgating constitutions or levying general taxes without the authorization of the three estates: the military, the church and nobility. Its mission was, amongst others, to control the King’s tax-related decisions. In order to collect the taxes approved by Les Corts, in 1359 a new institution was created, the Diputació del General, an embryo of the present Generalitat.

4. Crown of Aragon: a flourishing maritme power

In 1162, Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Barcelona, married Princess Peronella d’Aragó (Petronilla of Aragon), which led to the creation of the Crown of Aragon. During this period, an assembly known as the General Courts of Catalonia limited the King’s power. Between the 12th and the 15th centuries, the Crown of Aragon expanded its territory through Majorca, Valencia, Sicily, Sardinia, Naples and even Athens. It became a powerful military and commercial empire, which was administrated from Barcelona as a confederation in which each state had its own regulations. The Consulate of the Sea, a pioneering body for the administration of maritime and commercial law, was created. This institution’s documents became the code that ruled transactions in the Mediterranean for many years.

5. Dynastic union between Castile and Aragon

Isabel I de Castella (Isabella of Castile) and Ferran d’Aragó (Ferdinand of Aragon) married in 1469 and united their two realms in a single confederation. The Hispanic monarchs had to swear to respect the rules, constitutions and institutions of Castile and those of the several territories forming the Crown of Aragon.

6. First Catalan Republic, the War of the Reapers, and the Pyrenees Treaty

In 1640 Spanish King Felipe IV (Philip IV) forced Catalan peasants to host his army which was fighting against the French King Louis XIII. The peasants were angry about the treatment they were receiving and rebelled against Philip in the War of the Reapers (Guerra dels Segadors). Some of the most important noblemen ended up in prison. The Generalitat, led by clergyman Pau Claris, established the Catalan Republic, protected by France. It was to be short-lived, though – lasting only a few months. At the same time, Portugal benefited from the uprising and broke away from what we now call Spain. In 1659, the Treaty of the Pyrenees between France and Spain resulted in Philip IV giving part of the Catalan territories – Roussillon, Conflent and part of Cerdagne – to Louis XIV (this is the current French Département des Pyrénées Orientales ).

7. 1714: the end of the Catalan State

The War of the Spanish Succession (1701 – 1715) is considered one of the first global war conflicts. Apart from the succession of the Hispanic crown, there was also the question of the balance of power between the different European powers.

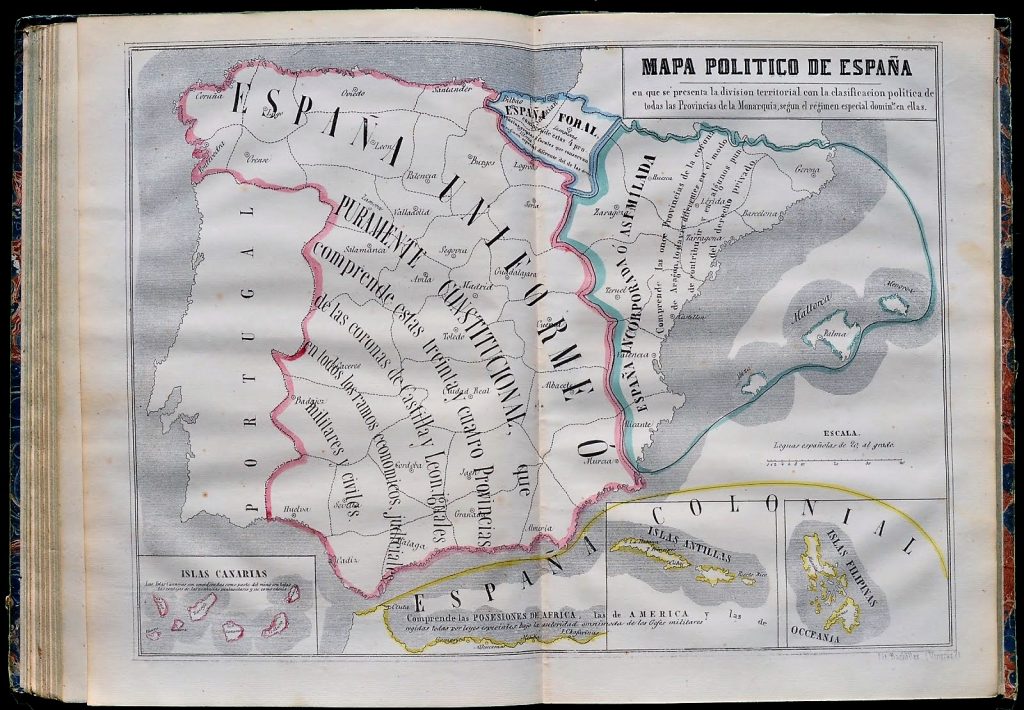

Within the Hispanic kingdoms, the Crown of Castile supported Felipe de Borbón (Philip de Borbon) while the states of the Crown of Aragon (Principality of Catalonia, Kingdom of Valencia, Kingdom of Aragon and Kingdom of Majorca) aligned with the pretender Charles of Austria, who offered to maintain traditional freedoms. For this reason, the triumph of Philip de Borbon (Philip V of Castile and Aragon IV), heir to French centralism, meant the end of the rights and privileges of the kingdoms of the Crown of Aragon, which were uniformed according to the laws of Castile.

With the fall of Barcelona, on September 11, 1714, Catalonia lost its governing institutions that it had maintained since the Middle Ages. In 1716, with the Nova Planta Decree, the king Philip de Borbon V annulled them legally and subjected Catalonia to the laws of the central power that entailed a great repression against the culture, languages and traditions of the Catalans that continued in reigns and successive dictatorships.

8. Napoleon and Catalonia

During the Napoleonic Wars, Spanish and French armies fought against each other over several years. At one stage in 1810 Napoleon allowed Catalonia to become an independent Republic under his guardianship. It was a period of sudden about-turns and in 1812 Napoleon incorporated Catalonia as part of his Empire until it became part of the Spanish Kingdom again in 1814 when the French were defeated.

9. The recovery of national consciousness: the Renaixença

During the 19th century, a cultural movement known as the Renaixença (Rebirth) promoted Catalan language, arts and architecture, with Antoni Gaudí as its most representative figure. Intellectuals, writers and artists took pride in Catalan culture and presented their works in Catalan. Parallel to the Catalan industrial revolution, the Renaixença was one of the boosting motors of Catalanism throughout the 19thcentury.

10. Recovering unity: the Mancomunitat

At the beginning of the 20th century, Catalonia regained its united administrative system and a certain degree of self-rule. Barcelona’s regional government leader, Enric Prat de la Riba, drove to reinstall a single institution to coordinate decisions among the four Catalan provinces and in 1914 the Mancomunitat was finally established. It was abolished eleven years later by the Spanish dictator Primo de Rivera in 1925.

11. Macià proclaims the Catalan Republic

In 1931, local elections were won by the left-wing republican party Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC). The leader of the party, Francesc Macià, proclaimed the short-lived Republic of Catalonia.

Three days later, he agreed with the newly-born Spanish Republic, the establishment of an autonomous government for Catalonia, under the name of Generalitat. Forced by these circumstances, King Alfonso XIII of Spain had fled into exile.

12. Franco’s military coup and the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War (July 17, 1936 – April 1, 1939) faced the democratic government of the Second Spanish Republic with a part of the army and with fascist organizations. The war began with a military coup headed by General Francisco Franco on July 17, 1936, which the next day spread throughout the state. The initial defeat of the coup participants in the main industrial centers, in Madrid and in the Mediterranean capitals, gave way to a long and bloody war that killed 500,000 people. It has been estimated that half a million Catalans crossed the French border; some returned, others stayed there, others exiled to Mexico, and many found death in concentration camps or in the new world war that was about to explode. The repression that came to Catalonia with the dictatorship of General Francisco Franco entailed executions, personal and family humiliation, economic plundering and second-class citizens, with duties but without rights. 4,000 Catalans were arbitrarily and systematically executed in Catalonia by the dictatorship.

13. A long period of facist dictatorship

Following the Republican defeat in February 1939, 500,000 people (200,000 of them were Catalans) were forced into exile and many would never come back. Lluís Companys, President of the Catalan Government, was executed in 1940 by firing squad, a unique case among elected presidents in European history. General Francisco Franco imposed a fascist dictatorship that lasted nearly 40 years. He abolished political parties and all democratic rights, such as freedom of speech and freedom of association. In Catalonia, Franco’s regime was especially fierce and he abolished the Statute of Autonomy and the Generalitat. The Catalan language and symbols were forbidden in all public sectors, schools and books.

14. Transition towards democracy: the Generalitat reinstated

At the beginning of the 1970s, calls for democracy and self-rule among groups of workers and students were on the increase. However, Franco’s dictatorship showed it was not open to change. Activists were sentenced to death and executed – as happened in the case of Catalan anarchist Salvador Puig Antich in 1974. The dictatorship finally came to an end with Franco’s death in 1975. During the following transition period, Catalan civil society mobilised to make its voice heard – in 1977 the first demonstration after Franco’s death was huge, with more than one million people marching through the streets of Barcelona and asking for freedom, amnesty and a new Statute of Autonomy. Before the new Spanish Constitution was passed, Josep Tarradellas, the President of the Generalitat elected in exile, returned to Catalonia on 23 October 1977. He reinstalled the Generalitat and set up an interim government. The Statute of Autonomy was promulgated on 18 September 1979.

15. Time for a new deal

Ever since the restoration of democracy in Spain and the devolution of limited self-rule to Catalonia, the main Catalan political parties have always been supportive of any efforts to consolidate democracy and to socially and economically modernize the Spanish State. Their involvement in Spain’s governance was evident with their support for different minority governments in Madrid, especially, when faced with big challenges like the accession to the EU or to the Euro. In 2004, when Spain’s democracy was seen as fully consolidated and the country was featured as one of the EU’s best examples of social and economic success, 90% of the MPs of the Catalan Parliament proposed to reform its Statute of Autonomy so as to consolidate Catalonia’s self-rule and finally find a suitable place for Catalonia within the Spanish State. The lack of a proper answer from the largest Spanish political parties to this proposal is probably the main reason why nowadays many Catalans are asking for a new deal.

16. Statute of Autonomy decimated by Spanish courts and beginning of the conflict for self-determination

In 2010 Spain’s Constitutional Court issued a landmark ruling that inadvertently laid the ground for Sunday’s independence referendum in Catalonia.

At issue was the 2006 Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia, a law passed by the legislature in the autonomous Spanish community, that was then approved by Spain’s parliament and later ratified in a referendum by Catalan voters. Almost immediately, the Popular Party, the center-right group that now governs the country, challenged the statute (parliament was then dominated by the Socialists) before the Constitutional Court. The court, Spain’s highest body for matters related to the constitutionality of laws, deliberated for the next four years. And its June 28 decision, on the face of it at the time, seemed harmless enough: Of the statute’s 223 articles, the court struck down 14 and curtailed another 27. Among other things, the ruling struck down attempts to place the distinctive Catalan language above Spanish in the region; ruled as unconstitutional regional powers over courts and judges; and said: “The interpretation of the references to ‘Catalonia as a nation’ and to ‘the national reality of Catalonia’ in the preamble of the Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia have no legal effect.”

The follow-up events are detailed in the self-determination conflict timeline.